Factsheet

Key Facts

- There are three main forms of leishmaniases: visceral (the most serious form because it is almost always fatal without treatment), cutaneous (the most common, usually causing skin ulcers), and mucocutaneous (affecting mouth, nose and throat).

- Leishmaniasis is caused by protozoan parasites which are transmitted by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sandflies.

- The disease affects some of the world’s poorest people and is associated with malnutrition, population displacement, poor housing, a weak immune system and lack of financial resources.

- An estimated 700 000 to 1 million new cases occur annually.

- Only a small fraction of those infected by parasites causing leishmaniasis will eventually develop the disease.

Leishmania parasites are transmitted through the bites of infected female phlebotomine sandflies, which feed on blood to produce eggs. Some 70 animal species, including humans, can be the source of Leishmania parasites.

WHO REGIONAL SPECIFICITIES

WHO African Region

All the three forms of the disease are prevalent in the region with various levels of endemicity seen in the countries. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis is highly endemic in Algeria whereas in west Africa the epidemiological information is scarce. In east Africa all forms of leishmaniasis are endemic with outbreaks of visceral leishmaniasis occurring frequently. Algeria, Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan and Uganda are known to be endemic for visceral leishmaniasis while the later five countries are among the high burden countries globally (http://www.who.int/wer No 45, 2022, 97, 575-590)[1].

For the region, access to diagnosis and treatment is generally limited due to weak health systems in the countries. In addition, there is a lack of accurate information on prevalence and spatial distribution of VL and VL case fatality rate in most endemic countries.

In 2021, 40% of the new VL cases were reported by EMRO, followed by 33% cases in AFRO. AMRO and SEARO reported 16% and 12% cases, respectively. During the same year, the East Africa eco-epidemiological foci (involving Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Uganda) reported 66% of all VL cases worldwide (http://www.who.int/wer).

Major challenges for the VL programme in the region include:

- Poor access to services

- Imperfect tools for diagnosis and treatment

- Weak reporting and inadequate surveillance system

- Limited country ownership

- Inadequate number of trained personnel

- Lack of proper supply chain management system

- Lack of proven effective vector control strategy

- Inadequate data on the prevalence of PKDL which is a reservoir of infection

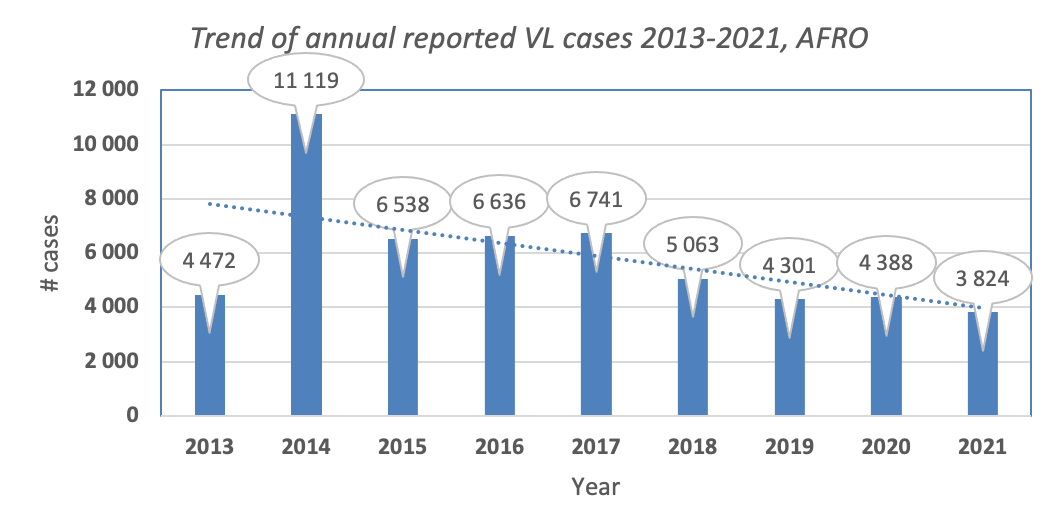

Figure: Trend of visceral leishmaniasis in the African Region (Source: WIDP)

WHO Region of the Americas

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the main form and the epidemiology is complex, with several animals being the source of the parasite, and numerous types of sandflies and multiple Leishmania species in the same geographical area. Brazil is the main country endemic for VL in that region.

WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region

This region accounts for 80% of the cutaneous leishmaniasis cases reported worldwide. Visceral leishmaniasis is highly endemic in Iraq, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen.

WHO European Region

Cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis are endemic. Imported cases are common, coming mainly from Africa and the Americas.

WHO South-East Asia Region

Visceral leishmaniasis is the main form of the disease, which is also endemic for cutaneous leishmaniasis.

[1] Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mauritania, Niger, Tanzania, Senegal, South Sudan, Uganda and Zambia.

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) is usually a sequel of visceral leishmaniasis that appears as macular, papular or nodular rash usually on face, upper arms and trunk. It occurs in east Africa (mainly in Sudan) and on the Indian subcontinent, where 5–10% of patients with kala-azar are reported to develop the condition. PKDL cases are reported from Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan and Uganda.

It usually appears 6 months to 1 or more years after kala-azar has apparently been cured but can occur earlier. People with PKDL are considered a potential source of Leishmania infection and hence require follow up after VL treatment for its occurrence and manage accordingly to prevent disease transmission and to contribute to the VL elimination target.

People living with HIV and who are infected with leishmaniasis have high chances of developing the full-blown disease, high relapse and mortality rates. Antiretroviral treatment reduces the development of the disease, delays relapses and increases the survival. As of 2021, Leishmania- HIV coinfection has been reported from 45 countries globally. High coinfection rates are reported from Brazil, Ethiopia and India.

In 2022, WHO published new treatment recommendations for Leishmania-HIV coinfected patients in east Africa and South-East Asia and being adapted by countries for use in case management.

- Socioeconomic conditions

Poverty increases the risk for leishmaniasis. Poor housing and domestic sanitary conditions (lack of waste management or open sewerage) may increase sandfly breeding and resting sites, as well as their access to humans. Sandflies are attracted to crowded housing because it is easier to bite people and feed on their blood. Human behaviour, such as sleeping outside or on the ground, may increase risk.

- Malnutrition

Diets lacking protein-energy, iron, vitamin A and zinc increase the risk that an infection will progress to a full-blown disease.

- Population mobility

Epidemics of leishmaniasis often occur when many people who are not immune move into areas where the transmission is high.

- Environmental and climate changes

The incidence of leishmaniasis can be affected by changes in urbanization, deforestation or the human incursion into forested areas.

Climate change is affecting the spread of leishmaniasis though changes in temperature and rainfall, which affect the size and geographic distribution of sandfly populations. Drought, famine and flood also cause migration of people into areas where the transmission of the parasite is high.

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL): is a systemic and chronic disease with common symptoms include fever, malaise, shivering or chills, weight loss, anorexia and discomfort in the left hypochondrium. The common clinical signs for VL are non-tender splenomegaly, with or without hepatomegaly, wasting and pallor of mucous membranes.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL): The clinical features of cutaneous leishmaniasis tend to vary depending on the leishmania species causing the disease, immunological status and also perhaps genetically determined responses of patients. The typical CL lesion starts as a papule or nodule at the site of inoculation. A crust may develop centrally to for ulcer and induration, which often heals gradually over months or years, leaving a depressed scar with altered pigmentation. Sometimes the lesion(s) can be big and severe and require treatment.

Picture showing cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion receiving intralesional therapy (Gondar hospital, Ethiopia, photo credit by Eleni Ayele)

Muco-cutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL): this is due to the involvement of the mucosal tissues of the mouth and upper respiratory tract by the leishmania parasites. It causes destructive and mutilation with obstruction and destruction of the nose, pharynx and larynx. It requires treatment with antileishmanial medicine and also antibiotics for secondary infections which are frequent.

People suspected of suffering from visceral leishmaniasis should seek medical care immediately. In visceral leishmaniasis, diagnosis is made by combining clinical signs with parasitological or serological tests (such as rapid diagnostic tests). In cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis serological tests have limited value and clinical manifestation with parasitological tests confirms the diagnosis.

The treatment of leishmaniasis depends on several factors including type of disease, concomitant pathologies, parasite species and geographic location. Leishmaniasis is a treatable and curable disease, which requires an immunocompetent system because medicines will not get rid of the parasite from the body, thus the risk of relapse if immunosuppression occurs. All patients diagnosed with visceral leishmaniasis require prompt and complete treatment. Detailed information on the treatment is available in the WHO technical report series 949, Control of leishmaniasis and the latest guidelines published on HIV-VL in east Africa and South-East Asia and the guideline for the treatment of leishmaniasis in the Americas.

Preventing and controlling the spread of leishmaniasis is complex and requires many tools. Key strategies include:

- Early diagnosis and effective prompt treatment reduce the prevalence of the disease and prevents disabilities and death. It helps to reduce transmission and to monitor the spread and burden of disease. There are highly effective and safe anti-leishmanial medicines particularly for visceral leishmaniasis, although they can be difficult to use. Access to medicines has significantly improved thanks to a WHO-negotiated price scheme and a medicine donation programme through WHO.

- Vector control helps to reduce or interrupt transmission of disease by decreasing the number of sandflies. Control methods include insecticide spray, use of insecticide-treated nets, environmental management and personal protection.

- Effective disease surveillance is important to promptly monitor and act during epidemics and situations with high case fatality rates under treatment.

- Control of animal reservoir hosts is complex and should be tailored to the local situation.

- Social mobilization and strengthening partnerships – mobilization and education of the community with effective behavioural change interventions must always be locally adapted. Partnership and collaboration with various stakeholders and other vector-borne disease control programmes is critical.

WHO's work on leishmaniasis control involves:

- supporting national leishmaniasis control programmes technically and financially to update guidelines, ensure access to quality-assured medicines, design disease control plans, surveillance systems, and epidemic preparedness and response systems;

- monitoring disease trends and assessing the impact of control activities through the web-based global surveillance system which will allow for raising awareness and advocacy on the global burden of leishmaniasis and promoting equitable access to health services;

- developing evidence-based policy strategies and standards for leishmaniasis prevention and control, including capacity building such as online courses at Neglected Tropical Diseases (openwho.org);

- strengthening collaboration and coordination among partners and stakeholders;

- promoting research including safe, effective and affordable medicines, as well as diagnostic tools and vaccines; and

- supporting the endemic countries in the WHO African Region, for the elimination of visceral leishmaniasis as a public health problem by 2030 as per the new WHO roadmap 2021-2030, defined as case fatality rate less than 1% for primary VL cases. The east Africa sub-region which includes also EMRO countries in the sub-region developed “Strategic Framework for Elimination of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Eastern Africa”.

Picture2: Stakeholders’ meeting for the Development of a Strategic Plan for the Elimination of VL in East Africa, Nairobi/Kenya, 24-27 January 2023, organized by WHO and END Fund.