Factsheet

Key Facts

- Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) called Sleeping sickness is caused by protozoan parasites transmitted by infected tsetse flies. It is endemic in 36 sub-Saharan Africa countries. Without treatment, HAT is generally fatal.

- Most exposed people live in rural areas and depend on agriculture, fishing, animal husbandry or hunting.

- HAT takes 2 forms, depending on the subspecies of the infecting parasite: Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (92% of reported cases) and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (8%).

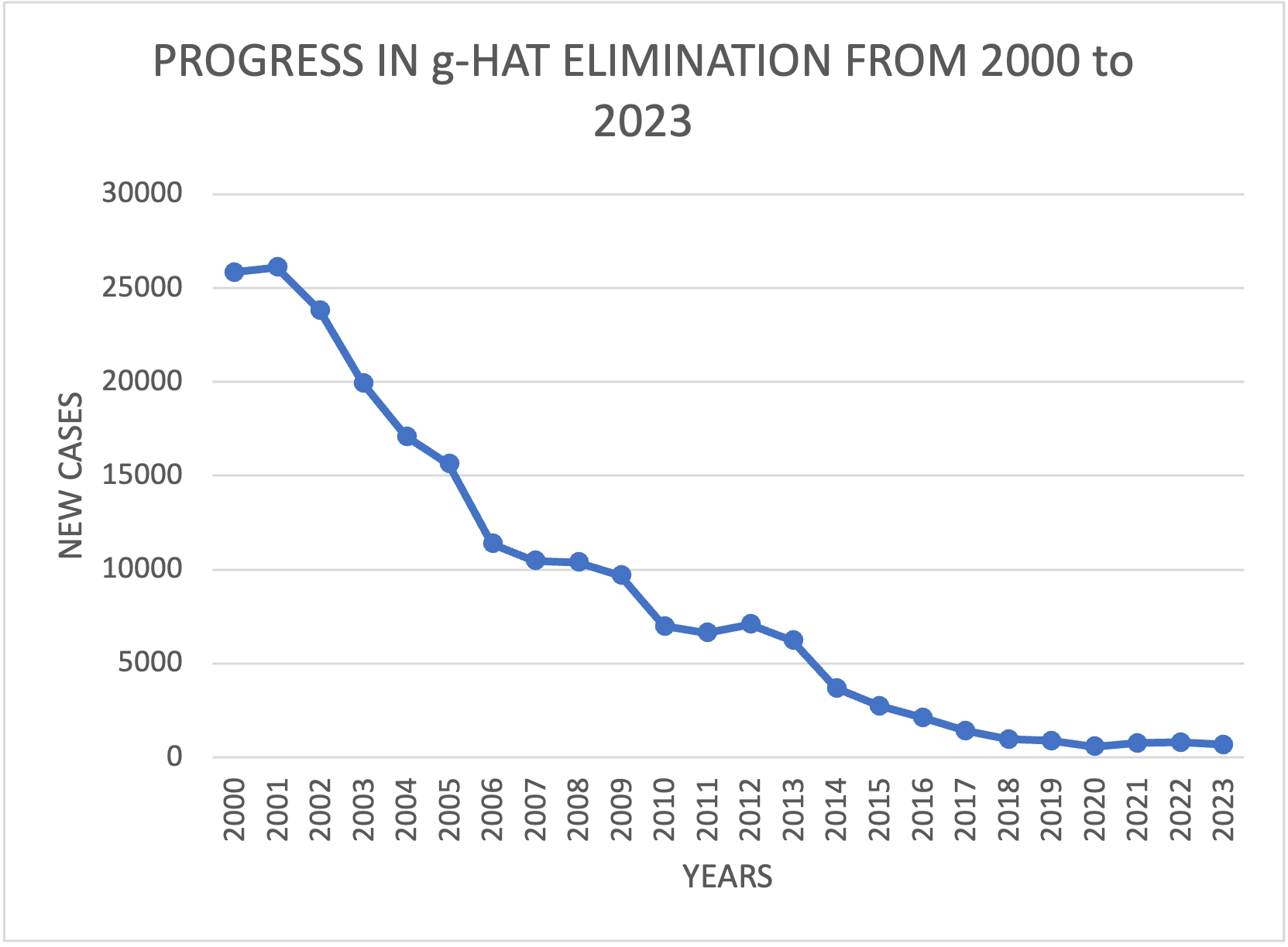

- Sustained control efforts have reduced the number of new cases by 97% in the last 20 years.

- Diagnosis and treatment are complex and require specific skills.

WHO plays a major role in defining strategies, supporting countries in their implementation, and advocating resource mobilization with partners and endemic countries alike.

Advocacy for the production and donation of trypanocides by pharmaceutical companies.

Facilitate collaboration and coordination between partners in the scientific sector (academics; researchers; producers, etc.) NGOs and implementing agencies.

In terms of interventions, between 2021-2023, countries were supported by WHO and partners to :

- Introduce new treatment guidelines with fexinidazole for gHAT and conduct training in 11 countries .

- Ensure that treatment is available for all detected cases

- Implement active pharmacovigilance of fexinidazole in those 11 countries

- Coordinate different stakeholders and co-organize with HQ the stakeholders’ meetings

(5th WHO stakeholders meeting on HAT elimination 7-9 June 2023)

- Supported sentinel surveillance of HAT ongoing in 19 countries

- Maintained HAT specimen bank and provided samples for different research institutions

- Support surveillance of rHAT in six endemic countries

- Facilitated staff training on HAT elimination strategies in Malawi and Uganda

In 2023 and 2024 we have continued to organize annual stakeholder meetings as well as the coordination of endemic countries and the various partners.

[1] Angola, Cameroon, Chad, Central African Republic, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, South Sudan and Uganda

[2] Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Senegal, South Sudan, Togo and Uganda

[3] Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe

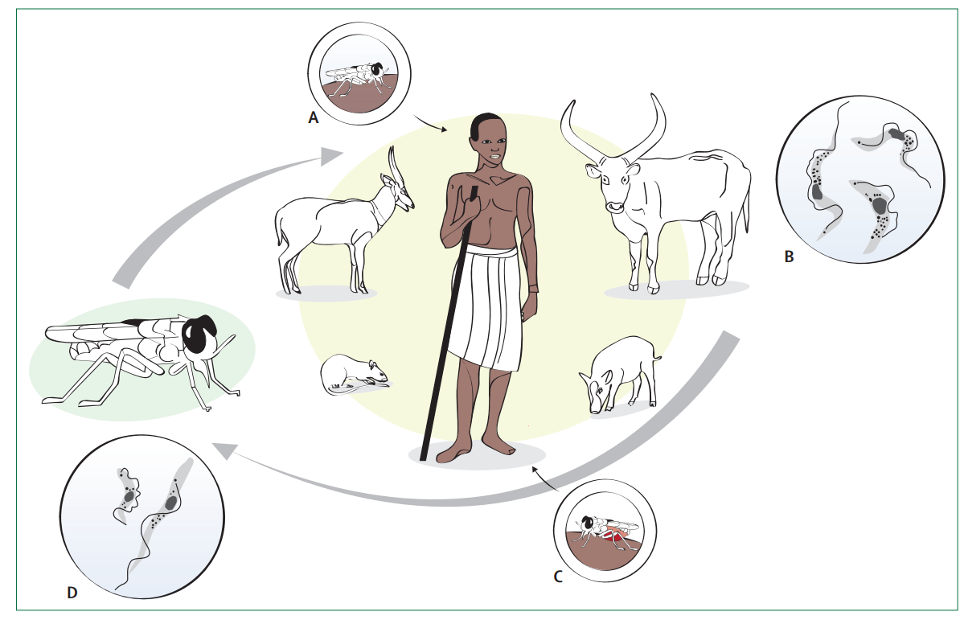

Human African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness, is a vector-borne parasitic disease. It is caused by infection with protozoan parasites belonging to the genus Trypanosoma. They are transmitted to humans by tsetse fly (Glossina genus) bites which have acquired their infection from human beings or from animals harbouring human pathogenic parasites.

Tsetse flies are found just in sub-Saharan Africa though only certain species transmit the disease. For reasons that are so far unexplained, in many regions where tsetse flies are found, sleeping sickness is not. Rural populations living in regions where transmission occurs and which depend on agriculture, fishing, animal husbandry or hunting are the most exposed to the tsetse fly and therefore to the disease. The disease develops in areas ranging from a single village to an entire region. Within an infected area, the intensity of the disease can vary from one village to the next.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), or sleeping sickness, is caused by trypanosome parasites that are transmitted by tsetse flies. HAT transmission requires the interaction of humans, tsetse flies and parasite reservoirs (humans, and domestic and wild animals).

For gambiense HAT, the main reservoir is other human beings. Rhodesiense HAT, however, is a zoonosis, a “disease or infection naturally transmitted between vertebrate animals and humans”. After infection, trypanosomes multiply in the blood and lymph (first stage, haemolymphatic) and, following a variable incubation period (from days to months),

Causative organism

Human African trypanosomiasis is caused by 2 types of parasites:

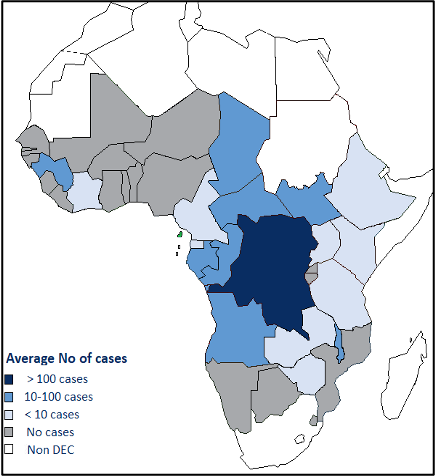

- Trypanosoma brucei gambiense in 24 countries in west and central Africa.

- Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense in 13 countries in eastern and southern Africa.

In 2012, WHO targeted the elimination of the disease as a public health problem by 2020. This goal has been reached and a new ambitious target was stated in the WHO road map for NTDs 2021–2030 and endorsed by the 73rd World Health Assembly: the elimination of gambiense HAT transmission (i.e., reducing the number of reported cases to zero). The interruption of transmission was not considered as an achievable goal for rhodesiense HAT, as it would require vast veterinary interventions rather than actions at the public health level

Significant progress has been made in the g-HAT elimination effort in the WHO Region for Africa. The annual number of cases reported in the region has dropped by over 97% from 25,841 cases in 2000, to 675 cases in 2023.

According to our target in 2021 -2030 Roadmap; 15 gambiense HAT countries must work for verification of interruption of transmission

- Lessons learnt from countries who were validated for HAT elimination, indicate that strong political will, sustainable funding for health, community engagement and health promotion, improved surveillance systems and multi-sectoral collaboration were key determinants in the elimination of HAT

- The adaptation of active HAT screening according to the epidemiological context and geographical accessibility by using mini-mobile units and door-to-door screening has made it possible to cover populations in hard-to-reach areas

In addition to the usual challenge of insufficient financial resources, some new challenges are:

- Maintaining the commitment of states and partners in the context where elimination is validated, and surveillance must continue

To detect and treat HAT seropositive people if possible

The TDR Diseases reference Group identified the following top research priorities for human African trypanosomiasis:

- Research on new diagnostics for case detection and characterization, including drug resistance and tests of cure.

- Research on new therapeutics to avoid drug resistance, including exploring combinations of approved anti-kinetoplastid drugs, repurposing of existing approved drugs, and developing new drugs.

- Research on new vector control technologies, including markers of successful vector control.

- Research on vector population characteristics, including insecticide resistance.

- Operational research on integrated disease and vector control.

- Research to assess the importance of asymptomatic infection.

With the list of new cases per village that endemic countries send to the WHO, a database called HAT ATLAS is managed in collaboration with the FAO.

- http://quarry.essi.upc.edu:8080/who/hat-distribution.html

- http://quarry.essi.upc.edu:8080/who/hat-risk.html

- https://apps.who.int/neglected_diseases/ntddata/hat/hat.html

- https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/hat-tb-gambiense

- https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/number-of-new-reported-cases-of-human-african-trypanosomiasis-(t-b-rhodesiense)

Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases

We are working to help achieve the targets of the Neglected Tropical Diseases Roadmap 2021 -2030; specifically for the elimination of HAT.