Factsheet

Key Facts

- Buruli ulcer is the third most common mycobacterial disease affecting humans, after leprosy and tuberculosis.

- The mode of transmission is not clear but somehow the bacteria get into the skin and start to grow and there is no prevention for the disease.

- In the African region, 12 out of the 47 member states are known to be endemic.

- Nearly half of the people affected in Africa are children under the age of 15 years.

- Integrated early detection and antibiotic treatment are the cornerstones of the control strategy.

Sources:

Data are from WHO : The Global Health Observatory and integrated African Health Observatory.

Photography: @WHO/Harandane Dicko | @WHO/Valerie Fernandezi, @WHO/Dr Yves Thierry Barogui.

Check out our other Fact Sheets in this iAHO country health profiles series: https://aho.afro.who.int/country-profiles/af

Fact Sheet Produced by: Monde Mambimongo Wangou, Berence Relisy Ouaya Bouesso, Sokona Sy, Serge Marcial Bataliack, Humphrey Cyprian Karamagi, Lindiwe Elizabeth Makubalo., Dr Yves Thierry Barogui, Dr Dorothy Achu.

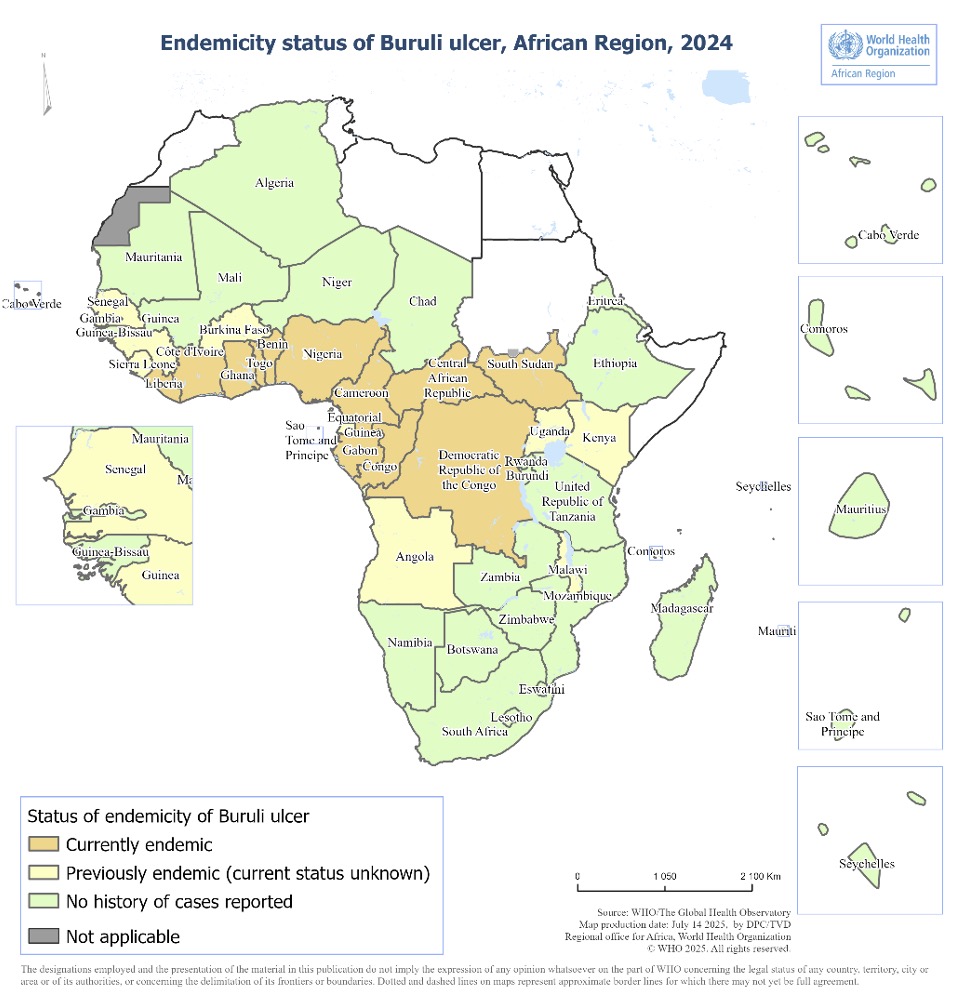

Status of endemicity of Buruli ulcer is declared in the countries have reported a case of Buruli ulcer at least once.

Figure 1. Status of endemicity of Buruli ulcer in the African Region, 2024 .

- The status of endemicity for Buruli ulcer in the African Region remains unchanged from 2022, with 12 of the 47 countries classified as endemic (Figure 1).

- 9 countries were classified as previously endemic for Buruli ulcer.

- Buruli ulcer primarily occurs in tropical and sub-tropical climate areas within the African Region.

Figure 2. Trend in the number of new reported cases of Buruli ulcer in the African Region, 2002-2024

- The average annual number of Buruli ulcer cases reported in the African Region was approximately 5,000 cases until 2010, when a consistent decline began.

- The reductions observed in 2020 and 2021 may be attributed to the impact of COVID-19, which disrupted active detection activities (see Figure 2).

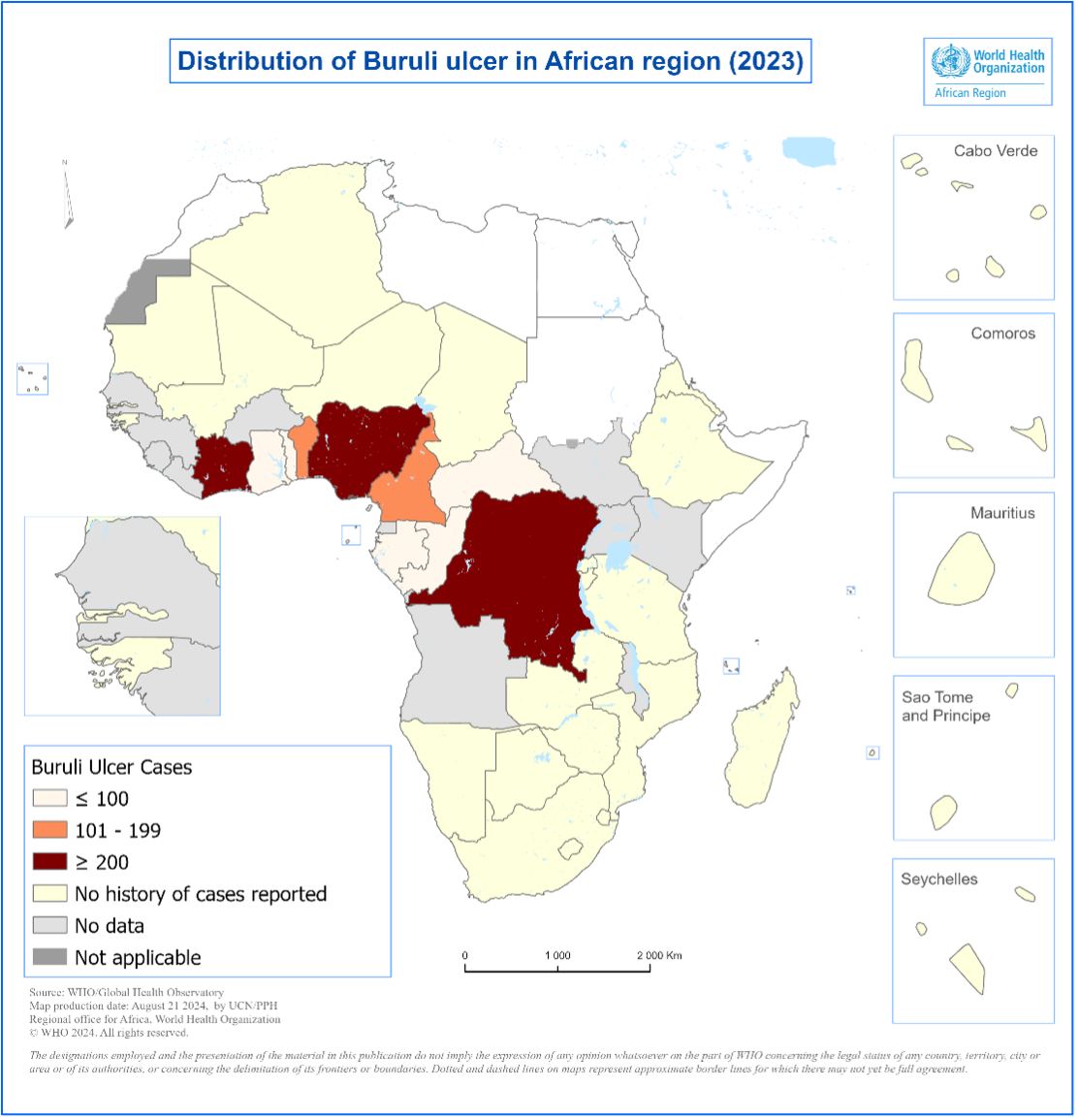

- In 2023, a total of 1,573 cases were reported from Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo (Figure 3).

- For further details on the country-specific trends of Buruli ulcer, refer to The Global Health Observatory.

The exact mode of transmission of Mycobacterium ulcerans (M. ulcerans) is still unclear. Buruli ulcer usually occurs near slow moving or stagnant bodies of water, where M. ulcerans is found in aquatic insects, molluscs, fish and the water itself. It is not clear how M. ulcerans is transmitted to humans.

Buruli ulcer often starts as a painless swelling (nodule), a large painless area of induration (plaque) or a diffuse painless swelling of the legs, arms or face (oedema). The disease may progress with no pain or fever. Without treatment or sometimes during antibiotics treatment, the nodule, plaque or oedema will ulcerate within 4 weeks. Bone is occasionally affected, causing deformities.

The disease has been classified into three categories of severity: Category I, single small lesion (32%) less than 5 cm on diameter; Category II, non-ulcerative and ulcerative plaque and oedematous forms between 5-15 cm (35%); and Category III lesions more than 15 cm in diameter including, disseminated and mixed forms such as, osteomyelitis and joint involvement, lesions at critical sites (head, breast, genitalia), (33%).

Lesions frequently occur in the limbs: 35% on the upper limbs, 55% on the lower limbs, and 10% on the other parts of the body. Health workers should be careful in the diagnosis of Buruli ulcer in patients with lower leg lesions to avoid confusion with other causes of ulceration such as diabetes, arterial and venous insufficiency lesion.

Differential diagnoses of Buruli ulcer include tropical phagedenic ulcers, chronic lower leg ulcers due to arterial and venous insufficiency (often in elderly populations), diabetic ulcers, cutaneous leishmaniasis, extensive ulcerative yaws and ulcers caused by Haemophilus ducreyi.

Early nodular and papular lesions may be confused with insect bite, boils, lipomas, ganglions, lymph node tuberculosis, onchocerciasis nodules or deep fungal subcutaneous infections. Cellulitis may look like oedema caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans infection but in the case of cellulitis, there is pain and fever. Four standard laboratory methods can be used to confirm Buruli ulcer: IS2404 polymerase chain reaction (PCR), direct microscopy, histopathology and culture. The bacterium grows best at temperatures between 29–33 °C (Mycobacterium tuberculosis grows at 37 °C) and needs a low (2.5%) oxygen concentration.

In 2019, WHO established the Buruli ulcer Laboratory Network for Africa to help strengthen PCR confirmation in 9 endemic countries in Africa. Thirteen laboratories participate in this network, supported by the American Leprosy Missions, Anesvad, Raoul Follereau Foundation and coordinated by the Pasteur Center of Cameroon.

In 2021, WHO completed an online consultation for a draft document on Target Product Profiles to develop rapid test for the diagnosis of Buruli ulcer. With the availability of simple oral treatment for Buruli ulcer, a rapid test to allow early confirmation of diagnosis can facilitate the timely treatment of the disease. The current turnaround time of a PCR test is too long to guide early treatment decisions.

Treatment consists of a combination of antibiotics and complementary treatments. A combination of rifampicin (10 mg/kg once daily) and clarithromycin (7.5 mg/kg twice daily) is now the recommended treatment. Interventions such as wound and lymphoedema management and surgery (mainly debridement and skin grafting) are used to speed up healing, thereby shortening the duration of hospitalization. Physiotherapy is needed in severe cases to prevent disability. Those left with disability require long-term rehabilitation. These same interventions are applicable to other neglected tropical diseases, such as leprosy and lymphatic filariasis.

The WHO has developed a treatment guidance for health workers.

HIV infection complicates the management of the patient, making clinical progression more aggressive and resulting in poor treatment outcomes. WHO has published a technical guide to help clinicians in the management of co-infection.

- The Yamoussoukro Declaration on Buruli ulcer

https://www.who.int/initiatives/global-buruli-ulcer-initiative-(gbui)/the-yamoussoukro-declaration-on-buruli-ulcer - Cotonou Declaration on Buruli Ulcer

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329410/WHO-HTM-NTD-GBUI-2009.1-eng.pdf - WHA57.1 Surveillance and control of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease (Buruli ulcer)

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/wha57.1

There are currently no primary preventive measures for Buruli ulcer. The mode of transmission is not known. Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) vaccination appears to provide limited protection.

The objective of Buruli ulcer control is to minimize the suffering, disabilities and socioeconomic burden. Early detection and antibiotic treatment are the cornerstones of the control strategy. In many countries, community health workers play a critical role in case detection.

These are the core indicators to measure the progress in the control of Buruli ulcer in the NTD road map 2021-2030.

- proportion of cases in category III (late stage) at diagnosis

- proportion of laboratory-confirmed cases

- proportion of confirmed cases who have completed a full course of antibiotic treatment.

- WHO. 2023. “Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection)”. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/buruli-ulcer-(mycobacterium-ulcerans-infection)

- WHO. 2023. “Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection) fact sheet”. Available at https://www.who.int/health-topics/buruli-ulcer#tab=tab_1

- WHO. “Buruli ulcer overview”. Available at https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/buruli-ulcer

- WHO. “Neglected tropical of diseases-Buruli ulcer”. Available at https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO/buruli-ulcer

- WHO. “Status of endemicity of Buruli ulcer”. Available at https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/buruli-ulcer

- WHO. “Number of new reported cases of Buruli ulcer”. Available at https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/number-of-new-reported-cases-of-buruli-ulcer

- WHO, 2006. “Recognizing Buruli ulcer in your community”. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69313/WHO_CDS_NTD_GBUI_2006.14_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- A road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030 ”. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010352

- “Framework for the integrated control, elimination and eradication of tropical and vector-borne diseases in the African Region 2022–2030”. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/361856/AFR-RC72-7-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=

- “Strategic framework for integrated control and management of skin-related neglected tropical diseases”. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240051423

- “Framework for development country NTD master plan 2021 - 2025 ”. Available at https://espen.afro.who.int/system/files/content/resources/NTDMasterPlan_Guidelines_WHOAfrRegion_Version3_160321.pdf

- “Laboratory diagnosis of Buruli ulcer ” . Available at https://espen.afro.who.int/system/files/content/resources/NTDMasterPlan_Guidelines_WHOAfrRegion_Version3_160321.pdf

- “Target product profile for a rapid test for diagnosis of Buruli ulcer at the primary health-care level”. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240043251

- “Treatment of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease (Buruli Ulcer) ” available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241503402

- “Standard recording and reporting using BU 01, BU 02 and BU 03 forms”. Available at https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/buruli-ulcer/objective-and-strategy-for-control-and-research#Reportingandrecordingforms

- Fourth annual meeting of the network of Buruli ulcer PCR laboratories in the WHO African Region, Mundi complex, Yaoundé, 24-26 October 2022. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077911

- Other publications ”. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i?healthtopics=46e0b136-0538-42f3-8761-190b7013265b&publishingoffices=ef806e9e-be4b-423a-91c9-9db2a8706e74&healthtopics-hidden=true&publishingoffices-hidden=true

Sources:

Data are from WHO : The Global Health Observatory and integrated African Health Observatory.

Photography: @WHO/Harandane Dicko | @WHO/Valerie Fernandezi, @WHO/Dr Yves Thierry Barogui.

Check out our other Fact Sheets in this iAHO country health profiles series: https://aho.afro.who.int/country-profiles/af

Fact Sheet Produced by: Monde Mambimongo Wangou, Berence Relisy Ouaya Bouesso, Sokona Sy, Serge Marcial Bataliack, Humphrey Cyprian Karamagi, Lindiwe Elizabeth Makubalo., Dr Yves Thierry Barogui, Dr Dorothy Achu.