The virus

Poliomyelitis, or polio for short, is a highly infectious viral disease. The virus, which mainly affects children under five, attacks the brain and spinal cord and can cause total paralysis within days of infection. There are three poliovirus serotypes, Type 1, 2 and 3 all of which have identical symptoms, for which there is no cure.

The virus is transmitted person-to-person mainly through the faecal-oral route, or less frequently through a common vehicle for example food or water that is contaminated with the virus. Once the virus has entered the body, usually through the mouth, it multiplies in the throat and intestines, and can also enter the bloodstream and spread to the nervous system. Although children are more likely to catch polio, adults - who often carry the virus without displaying symptoms - help to spread it. Environmental factors including poor sanitation can also help spread the virus.

Symptoms and diagnosis

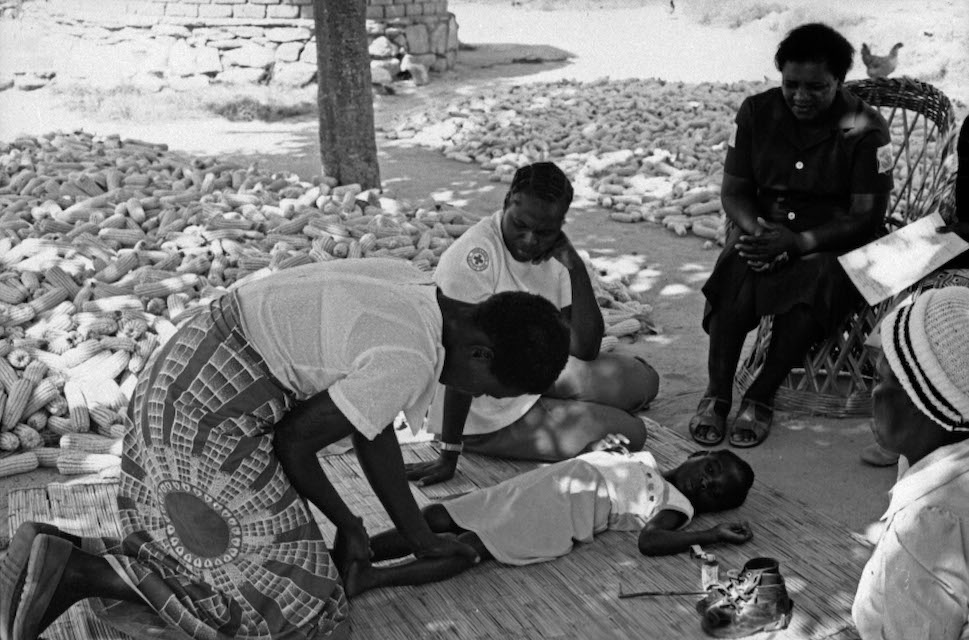

The majority of people the virus infects do not show any signs of infection, though some experience symptoms, which include sudden onset of fever, tiredness, headache, vomiting, stiffness of the neck, aching muscles and pain in the limbs. In a smaller number of cases, the virus invades the central nervous system, causing paralysis, usually in the legs and sometimes in the arms. For many, this is only temporary, and the sufferer regains movement over time, usually within weeks or months. For others, however, the paralysis—known as acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) - is irreversible. In rare cases this results in death when the breathing muscles become immobilised. Around one in 200 suffer permanent paralysis, and five to ten percent among those paralysed die.

For the majority who survive there can still be life-long complications. Sufferers may have permanent deformities, such as twisted legs or feet, weakness or shrinking of the muscles, or tight joints. Some experience post-polio syndrome: a poorly understood condition that sees symptoms return years after the sufferer recovered from the infection and that affects even those who had no symptoms at the time that they had polio.

Polio vaccines

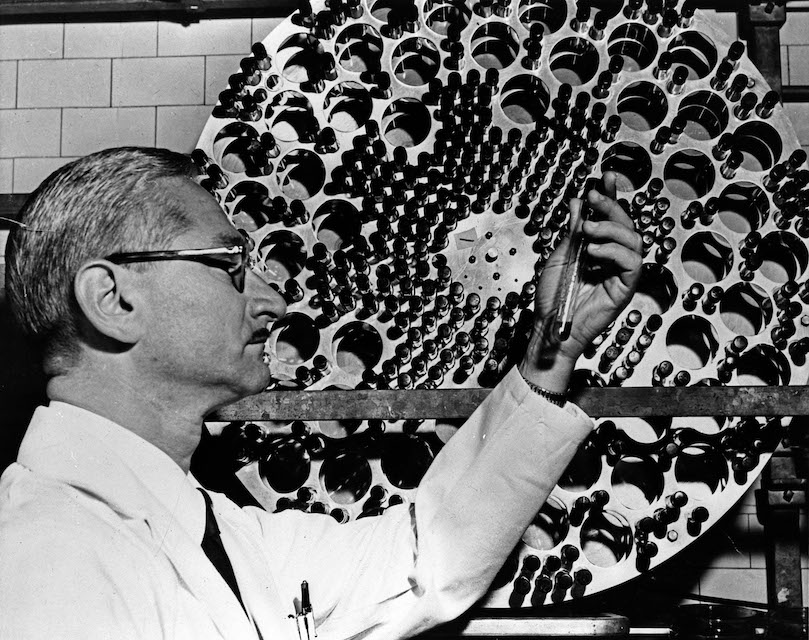

The development of vaccines for polio was one of the major breakthroughs of the twentieth century. The first effective injectable polio vaccine was produced in Pittsburgh in 1955 by Dr Jonas Salk, following which the United States launched the first mass immunization campaigns. An oral vaccine, developed by Dr Albert Sabin came onto the market in 1961. With these two life-saving innovations, eradication became possible.

There are two types of vaccines used to stop the spread of polio. The inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which is injected, contains deactivated viruses and creates antibodies in the blood. Used in industrialised, polio-free countries, it has a few drawbacks, namely that while the vaccinated person is protected from the disease, if the virus enters their gut it can still be passed on to others through the oral-faecal route for several weeks after the vaccination is administered. It is therefore less effective in high risk areas with lower levels of vaccination in the community.

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) contains the weakened live virus and creates antibodies in the gut rather than the blood. Given in two doses during routine immunization and three doses during supplementary immunization activities delivered up to a month apart, OPV provides lifelong immunity to polio. As such, even if the vaccinated person consumes food or water contaminated with polio virus in the few weeks after it is administered, the vaccine antibodies in the gut fight the wild poliovirus when it enters through digestion. This means that the OPV not only protects the individual child, but also offers more protection to the community than the IPV.

OPV is also more suited to low-resource settings: unlike the IPV, it does not require expensive sterilized syringes nor special skills to administer it, so immunization campaigns can easily be rolled out by volunteers with minimal training.

When enough people in a community are immunized against polio, the virus is deprived of susceptible hosts and dies out. At least 90% of children should be fully vaccinated to make sure that the disease doesn't spread among the population if it is reintroduced, as just one infected child can start an outbreak.